“We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.” ~ Anaïs Nin

Democracy, I once told my International Management class, is not about the fact that “the majority rules“, but rather, that no matter the circumstances of your birth, you have a right for your voice to be heard and to seek to have that voice represented in government. I demonstrated this concept with some beautifully decorated cupcakes which I brought to class specifically for this purpose. I took two cupcakes and put them on a separate plate. I then took the plate with the two cupcakes and placed it with force on top of the other plate smashing the other cupcakes. I was, however, baffled by the reaction from my students. Instead of prompting a serious conversation about the pros and cons of this understanding of “democracy“, they were more interested in what I plan to do with the ruined cupcakes. Perhaps it was because I failed to kindle their interest in the topic, or because it was simply near their lunch hour and the cupcakes – still perfectly edible – was an opportunity not to be missed for students who typically have to live on a small budget.

In retrospect, the missed opportunity was more mine. I had an opportunity to help my students understand an opposing view of democracy, which I did not do. My students’ reaction, I have come to understand, was actually aligned with our context at the time. Most of the students came from South Africa and from other African countries. Many citizens in these developing nations are preoccupied with their own economic needs, and have no reason to favour political modernisation and democratisation. They are more concerned with “what is in it for me?” and furthermore do not want to look like they are supporting something that implicitly means support for Western income levels and living standards. Many African countries with non-democratic regimes embrace the term democracy because of its positive connotations without really understanding its meaning.

By wanting to offer a different perspective that day, I certainly didn’t want to create the impression that I favour an “epistemological anarchism” in which “anything goes”. Rather, I believe that we should recognise that perspectives may evolve with changes in goals and context and that we should pursue standardised and rigorous perspectives (by this I do not mean a single correct or “best” perspective) in conjunction with a realistic focus. I believe it is more realistic to gain insight from mutually agreed upon information, acquired through rigorous thought processes and conscious choices. Thus, choices from a range of alternatives, which, although they are justified in light of certain context-specific criteria, still allow you to recognise the validity of other decisions in other contexts.

Let’s consider how the concepts ‘perspective’ and ‘reality’ relate. There are many expressions around this topic. A well-known one is “my perspective is my reality” which equates the two concepts. But, is this the best line to take? Perspective is the way you see the world. It comes from your personal point of view and is shaped by your life experiences, your values, your current state of mind, the assumptions you bring into a situation, and a whole lot of other things. Reality, however, can be different things. Even though there is truth to the statement that my perspective is my reality, when we look at the shared reality of say an event, the more perspectives you get the closer to reality you get. Can you therefore really afford to limit your perspective to your own reality only?

Throughout your life, you will be exposed to perspectives and realities beyond your own. You cannot foolishly cling to your own perspective or, for that matter, accept the first viewpoint that comes along. You should rather explore different ways of looking at what is right in front of you. It is about questioning assumptions and removing blinkers; about not being trapped by context, past experiences or emotions. It is about looking at a situation from above and below, forwards and backwards. It’s about resisting being critical, and seeking to generate lots of alternative solutions, even when you think that you already have the answer. It is about seeking a perspective that few others will take and looking where other people don’t look.

To be open to multiple perspectives or to ‘remove your blinkers’, you require two primary skills, namely perspective taking and perspective seeking. Perspective taking is the ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes and to consider how you affect others. Perspective seeking, on the other hand, is the ability to reach out to people to better understand their point of view on a specific topic or situation. It is about being truly and authentically curious about hearing and learning more about their perspective.

In the novel ‘To kill a mockingbird’ by Harper Lee, Atticus tells the children that they need to walk in someone else’s shoes before judging them, “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view… until you climb in his skin and walk around in it.” Perspective taking requires a concerted effort. Normally we do not respond to “the world out there”. We respond to our perception of the world. When we listen to someone talk, we are hearing our perception of this person’s words, gestures and so forth. We are making meaning out of what the person communicates based on that. This may or may not match the meaning intended. If we are offended by what the person says, we are actually offended by what we did with the person’s words, based on how we made meaning out of them. Essentially, the person-in-us, and not the real person, offends us. Walking in someone else’s shoes will change your perception of the situation, like it changed the children in ‘To kill a mockingbird’s’ view on the situations going on around them. Just like they did, we will learn a sense of sympathy and compassion, and gain a new perspective. The Dalai Lama concurs, “When you talk, you are only repeating what you already know. But if you listen, you may learn something new”.

While perspective taking occurs in your own head, perspective seeking is a dialogue where you ask other people about their experience, their opinions, their ideas, in a way that is respectful and helps build engagement, collaboration and a sense of being “in it together”. Seeking and integrating perspectives is vital for dealing effectively with complexity.

Now that you can consciously listen to the perspective of others, can you see it simply as a perspective? Not as something good or bad? The biggest trap of perspective seeking, is reaching out to people who have the same point of view as you, to validate a hard decision you want to make. The richness of using this skill is actually hearing from the people who may have a different point of view from yours, and discovering potential blind spots, or new things to consider. For as Mark Twain says, “Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect”.

Sometimes, however, the perspectives are total opposites. This type of situation is charmingly illustrated in Fiona Roberton’s children’s book ‘A tale of two beasts’. In the book, a little girl rescues a strange beast in the woods and carries him home. However, the beast escapes. Rather unusual for a picture book, the story is told from two different points of view. Two funny and charming tales emerge about seeing both sides of the story.

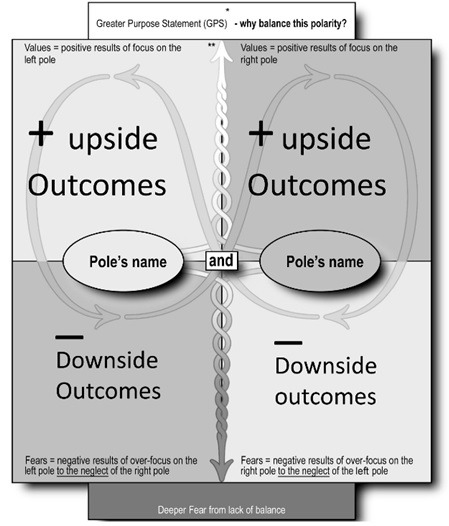

The challenge now becomes how to handle opposing views (a polarity), while not seeking a single correct or “best” view. Thus, finding a situation where you get the best of both worlds. A polarity is something that is two parts of the same whole, e.g. democracy versus non-democracy. You cannot have one without the other. However, we tend to lean into one or the other. What should we rather do?

Barry Johnson says that we should map the polarity, i.e. understand the upsides of one thing and the upsides of the other, and the downsides of the one and the downsides of the other (see a polarity map below). Then try to understand where you stand – at either the left or the right pole.

Now guide yourself and your own actions on the map to get the best of both worlds (from either an “A” or a “B” position). What usually happens, however, is that if we see a problem we fall into the downsides and in response pull ourselves up into the upsides of the opposite pole.

If you do this too hard, you fall into the downsides of that pole. And when that happens, it’s a confusing and divided situation to be in.

Then you pull up into the opposite of the top halve of the oppose pole. If you do that too hard, you fall down into the downsides of that pole. Then, the whole process starts again creating an immune system that drops you in the bottom half of both poles to get all the bad stuff of both poles. This can get you quite stuck.

If, however, you treat the opposing perspectives as a polarity to be managed, instead of a lurching problem to be solved, you can lift that whole pattern up into the upside of both halves.

You’ll get the great things of both poles together, by leaning gently one way or the other, paying attention to weak signals that you might be leaning to hard, and then by trying small experiments along the way; helping to get the best of both worlds (making the pattern of an infinity loop).

Seeking multiple or different perspectives is, according to research by McKinsey and Company, one of the most impactful leadership traits today – a foundational point that has been popularised well over the last few decades. Steven Covey’s fifth habit is “seek first to understand, then to be understood”. Covey’s point seems so easy and, yet, is one of the most difficult things to actually do. We are so set in our ways that it is easy to think we are seeking the other side, when actually, we are just biding time until the other side stops, and we can then make our point. The difficulty is that the other side senses this, and this can make problem solving difficult. One of the best ways to connect with other perspectives is to become an expert on the art of asking good questions. The book ‘A More Beautiful Question’ by Warren Berger, is a great resource for learning this in depth.

The trouble is that often you are in such a hurry to get to a solution that you just “ready-fire-aim”. What you should do, is to slow down the process by asking – using Berger’s suggested questions as guidelines – the following three questions: (1) Why am I thinking this way?, (2) What if I think in another way?, and (3) How would I do that? This will help you to think in a wider mode. Einstein understood this, as is evident from when he said, “If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions”.

Another problem is that we often find it very difficult to stop and consider other people’s perspectives when we are in the midst of a heated conversation. After all, why would you consider other perspectives when you’re right? Well, the thing is, many times when we think we’re right (and we are) so is the other person. It’s indeed possible that people can disagree, but both be right. It’s after all a matter of perspective.

When I tried to teach my students about democracy, I did it from a closed perspective (with blinkers on). After seeing their reaction, I did not stop talking, listened, and asked questions to begin to understand their perspective. By seeking their perspective (even if it is a skewed and distorted version of reality), they could have come around to seeing the perspective I’d put to them. Taking time to understand different perspectives, is the only way to resolve any situation without (or at least with less) lingering animosity.

The lesson here, is to first allow your mind to have thoughts, but instead of chasing them, to sit back and acknowledge them without any judgement. By doing this, you take a perspective on your own thoughts, ideas and beliefs that you previously may not have had. Secondly, by listening to other (multiple) perspectives without being judgmental, you will begin to see that other perspectives might actually make sense; even if you don’t necessarily agree. Rising to this level of understanding, can lead to less stressful and calmer conversations, interactions, and lives.

Just as self-awareness is the first step to making any change in an individual’s attitudes and behaviours, awareness of multiple perspectives can help LEAP Thinkers make an informed decision to initiate transformation, even if it seems conflicting.

Even when multiple perspectives exist, there is always a predominant perspective that drives decision-making. It doesn’t mean that these perspectives are mutually exclusive. Knowing the perspectives and actively allowing a perspective to germinate is what is required. On The LEAP Journey, LEAP Thinkers are exposed to fresh perspectives in order to move to the next transformational level. Holding on to deeply ingrained beliefs, will limit an individual’s transformation. Rather, personal perspectives should be managed by being open to other perspectives, forming new ones, and living those new perspectives. Until it is time for change… Perspectives change all the time, you evolve, your circumstances change, the world changes. It’s a journey…

More times than not, transformational programs treat the subject from one specific perspective; be it from the theories of neurology, theology, philosophy or psychology. On The LEAP Journey, we delve deep into various complex theories, integrate them, and discover truths that will not only change your perspective but, if applied, will transform the trajectory of your entire life and career. All that is required from you is to “remove your blinkers” and join the journey…

References:

- Berger, W. (2014). A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Covey, S.R. (2013). The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. New York: RosettaBooks.

- Johnson, B. (2011). Polarity Management: Identifying and Managing Unsolvable Problems. Amherst, MA: HRD Press.

- Lee, H. (2014). To Kill a Mockingbird (Harperperennial Modern Classics). London: Arrow Books.

- Roberton, F. (2015). A Tale of Two Beasts. London: Hodder Children’s Books.

- Tavris, C. & Aronson, E. (2015). Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts. Wilmington: Mariner Books.

- Wiseman, R. (2004). Did you Spot the Gorilla?: How to Recognise Hidden Opportunities. London: Arrow Books.